Ahmad Nawash (1934-2017)

Pillars of Fine Art Movement in Jordan

Born in Jerusalem in 1934, Ahmad graduated with honors from the Accademia di Arte in Rome (1964) and attained a degree from the E’cole des beaux Arts in Bordeaux where he studied graphics and etching (1970).

The artist spent two years at the E’cole National des Beaux Arts in Paris (1975-77) and later moved to Italy for a shot course in etching and pottery preservation.

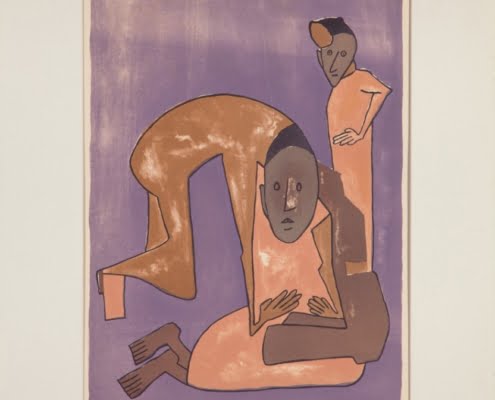

The subjects that the artist depicts in his paintings are mostly socio-political and humanitarian issues which are portrayed through his own symbolic language.

Ahmad Nawash is considered one of the big artists in Jordan and his talent is very appreciated in the Jordanian art movement.

Since 1964, Nawash has held numerous solo exhibitions in Rome, Paris, Jerusalem, Baghdad, and Amman and has participated in a large number of group exhibitions in Jordan and abroad.

“The work of Ahmad Nawash, known both in the Arab world and abroad, constitutes a comprehensive discourse in which he has opted for artistic integrity. He has quietly made his mark on the Jordanian art scene by insisting on honesty in his depictions. In the early phases of his work, he experimented, as did many of his contemporaries, with a variety of artistic directions, especially cubism and expressionism. However, although nature and the human figure remain foremost in his compositions, continuous and thorough research, sometimes academic, has lead him to what we might call a ‘spontaneous style’. As the artist himself has indicated, it is not the content itself which is spontaneous. What is presented is a particular vision of the world, its contradictions, disruptions and overall totality, transformed into complex aesthetic associations that are represented by altered human and animal figures.” Talal Moualla

“In The Palestinian Cause (Golda Meir and the Funeral) from 1973, Nawash also addresses the martyrdom of the national body. A Palestinian flag covers a cild’s sized coffin. The pallbearer on the left is a pair of feet that shares the martyr’s head and dangling arm. At its other end, the coffin merges with the upright body of an awkwardly leaning woman who wags her finger over the child in a parody of Muslim benediction for the dead. Three other figures populate the scene. One of these is lopsided like the gesturing woman and shares a leg with her. Another sports an armless rectangular trunk. The body of the third consists of an oval encircled by a band and sprouting tiny, pointy feet. You could see in these figures a dead cild, a mourning mother (upper left), an emasculated (disarmed) father (lower right), and a pair of aggressors who have arrogated to themselves the role of pronouncing the meaning of death.

What is important to keep in mind is the inevitably tentative quality of such attributions. To tidy them into secure identities would be to ignore Nawash’s deliberately ambiguous style. Beyond a few emphatically nationalist symbols – such as the Palestinian flag – Nawash’s figures are rarely ethnically identifiable. They are more distinctive for how they cavort playfully with figures from paintings by Juan Miro and Pablo Picasso. They are disproportional, fragmented and absurdly conjoined. A single anatomical mass by merge three bodies so that one head shares three postures, or the torso of one may share the legs of his aggressors. It is as if Nawash sought to show the ambivalence and confusion inherent in this type of embattled existence. Nevertheless, titles such as The Uprising and The Palestinian Cause firmly direct the itinerary of French Cubist and Surrealist modernism into his native territory. Where the Arab body meets brutal occupation and colonialism, it also meets high art and universal modernity. Both facets are visually present in Nawash’s work. Each is representable and gains density, in relation to the other: modernism becomes universal by arising in non-metropolitan settings, and Arabs become makers and subjects of high art by importing metropolitan styles.”